California Agricultural Technology Institute

Professor's new "cocktail" aims to expand nematode control

In agriculture’s seemingly unending battle against plant eating pests, a Fresno State biologist is conducting his own long-term effort to help control one tiny pest group called nematodes, and he is hopeful that a breakthrough will come soon…

Dr. Alejandro Calderón-Urrea is in his 14th year of devising new biological methods to reduce nematode populations in soils. His work is gaining more and more significance, as one of the most dependable chemical controls now in use – methyl bromide – is facing ever-tightening restrictions by government regulators because of it toxicity to the environment. It soon may face complete restriction, which would be a huge blow to growers of vegetables to grapes, even orchard crops.

Growers are happy to get rid of it as well, but their problem is finding an effective

alternative for controlling the pest – one that will not harm other organisms or the

environment.

Growers are happy to get rid of it as well, but their problem is finding an effective

alternative for controlling the pest – one that will not harm other organisms or the

environment.

Nematodes are tiny worm-like creatures. Of the many different species, most are the size of a pin head, or smaller. In agriculture they feed mainly on plant roots, causing serious damage to the plant. In California they attack everything from common garden plants such as tomatoes, to commercial vegetable crops, grape vines and fruit trees.

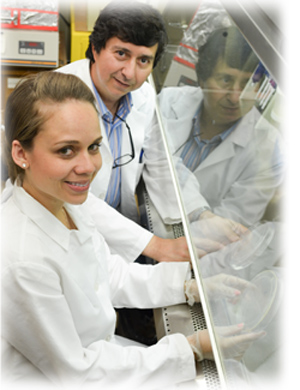

At left, Dr. Calderón-Urrea and undergraduate student Caroline Vidal prepare Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) worms to conduct bio-assays with organic chalcones.

“Each crop has a specific species of nematode that infects it,” Calderón-Urrea said. “We used to use methyl bromide which is very effective. The downside is that it kills every single living organism in the soil, including the good bacteria. Then the good nutrients are not available to the plant.” Evidence shows it is also a danger to humans as well as to the ozone layer, he noted.

With startup grant funding from the California State University Agricultural Research Institute in 2001, Calderón-Urrea began research on certain natural protein materials that when fed to one species of nematodes, affected their metabolic system in such a way to cause “programmed cell death” (PCD) and death of the pest.

“The proteins affect the expression of certain genes in the organism, causing cell suicide. We still don’t know how it works, we just know it works,” Calderón-Urrea said. The problem so far has been that the method worked only on a single species, Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), which is a non-pathogenic species used essentially for laboratory work.

The goal now is to develop a single or a combination of proteins and chalcones – organic derivatives from plant

products – that are effective against a broader set of nematode species.

single or a combination of proteins and chalcones – organic derivatives from plant

products – that are effective against a broader set of nematode species.

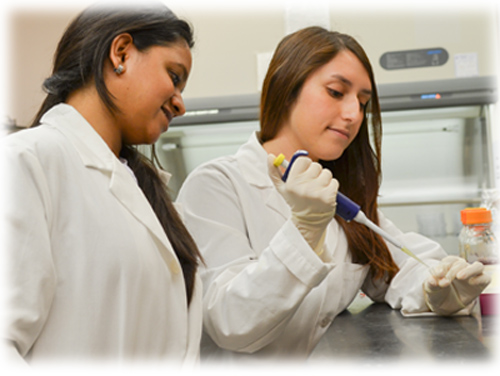

At right, undergraduate student Miriam Hernandez (right) and graduate student Yesheswi Chavan prepare dilutions of organic chalcones.

“Our approach is to develop a cocktail that includes combinations of the protein known to kill nematodes and specific organic chalcones” he said. “So far we have developed eight different chalcones with different effectiveness. Now we want to mix them and see if they work independently or if they have a synergistic effect.”

The ultimate goal is to use biotechnology to develop an effective cocktail, which can be effective triggering nematode suicide without harming the plant. When the cocktail is applied to the soil the nematodes will ingest the components and voilá – nematode death. This control method would be nematode specific and would cause no harm to other organisms. “We don’t want to kill the good organisms,” Calderón-Urrea said.

Student research assistants have played a significant role in the continuing research, Calderón-Urrrea said. Over the years more than a dozen students have conducted laboratory work, some as part of their course work, some as paid research assistants, and some simply volunteering to gain research training. Five students have completed theses projects related to nematode research.

Calderón-Urrea is seeking additional grant funding to support the new phase of research in developing an improved protein cocktail that will control nematodes specifically pathogenic to agriculture.

“This is a lofty goal, but this is what we’re trying to do,” he said.

For more information on this or his related research, contact Calderón-Urrea at calalea@csufresno.edu.