California Agricultural Technology Institute

CAB provides input on issues

University economists increasingly called upon to provide independent analysis of complex issues

Economists from Fresno State s Center for Agricultural Business (CAB) and partnering

research institutes have released resource information on critical food safety and

transportation issues affecting California s agricultural industry.

Economists from Fresno State s Center for Agricultural Business (CAB) and partnering

research institutes have released resource information on critical food safety and

transportation issues affecting California s agricultural industry.

In one case, CAB Director Mickey Paggi joined with colleagues from the Department of Agricultural Economics at Texas A&M University to conduct an economic analysis of the costs to the industry of foodborne illness outbreaks. In another case Paggi teamed with CAB senior economist Fumiko Yamazaki and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo Associate Professor Sean Hurley to analyze fresh produce transportation modes and their relative greenhouse gas emissions.

The economic analysis is part of a larger study of California specialty crop transportation funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Such support reveals a growing reliance by agencies such as the USDA on independent assessments of industry trends, Paggi noted.

The portfolio of issues facing California s agricultural industry increasingly includes consumer concerns about food safety and the environment, he said. These challenges are expanding the scope of research and analysis in the areas of production, marketing, trade and policy.

The food safety analysis focuses on case studies of three widely publicized foodborne illness outbreaks in the United States during recent years. Those cases all caused by bacterial contamination included the bagged spinach outbreak of September 2006, which killed three people and sent 104 to hospitals across the United States; the cantaloupe outbreak of March-April 2008, which sickened at least 50 people across 16 states and sent 14 to hospitals; and the so-called tomato outbreak of June-July 2008, which triggered 1,200 reported cases of salmonellosis across nine southwestern states.

|

|---|

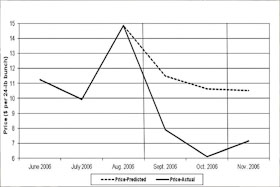

| Time series plots of spinach prices from June through Nov. 2006. Vertical lines of interest are Sept. 2006 (beginning of food scare) and Oct. 2006 (ending date of food scare). |

The tomato outbreak was eventually traced not to contaminated tomatoes but to jalapeno and Serrano peppers, but by the time that was discovered the illness outbreak had subsided and the damage to the tomato industry had already been done.

In each case, while the illnesses and deaths were tragic, the damage to entire segments of the farm industry as a result of mistakes or poor practices by individual operations was enormous, Paggi noted. U.S. spinach farm losses in that case were calculated to be $12 million; losses to the cantaloupe industry in 2008 were estimated at nearly $6 million; and farm level losses to U.S. producers from the tomato case were $25 million.

Outbreaks of foodborne illnesses have increased fears about the effectiveness of protective measures designed for food safety assurance, Paggi noted in the report. This has prompted both government agencies and industry associations to develop and enforce more strict and costly regulations aimed at preventing outbreaks and more effectively tracing them when they do occur, he said.

While compliance costs for these programs add considerably to the production costs of growers, economic analyses taking into account projected industry losses as a result of illness outbreaks found that compliance pays off in the long run.

Costs of compliance with these new standards are an up-front, added cost of doing business, Paggi said. However, projections indicate that the benefits over time will outweigh the costs by reducing adverse revenue effects due to an outbreak incident, reducing legal liability and insurance costs, and improving overall operational efficiency, the researchers concluded.

The complete analysis will be published as an article in the April 2012 volume of Hort Technology, a peer-reviewed outreach publication of the American Society for Horticultural Science.

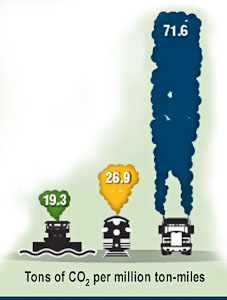

In a second report, presented to the U.S. Food Distribution Research Society, Paggi gave information on greenhouse gas emissions generated by food product distribution across the United States.

In a study of the three primary transport systems, the research team found that truck transport produces farm more carbon dioxide per ton of product moved than do rail or barge systems.

The dominance of truck transport imposes a definable transportation carbon footprint,

Paggi said in his report. At the same time, alternative transport scenarios are difficult

if not impossible in the foreseeable future. Why? Truck transport is the most effective

and timely method for moving large volumes of perishable products from farm to market,

whether locally, regionally or nationally.

The dominance of truck transport imposes a definable transportation carbon footprint,

Paggi said in his report. At the same time, alternative transport scenarios are difficult

if not impossible in the foreseeable future. Why? Truck transport is the most effective

and timely method for moving large volumes of perishable products from farm to market,

whether locally, regionally or nationally.

In an attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, some countries, such as the United Kingdom and Australia, are considering implementing a carbon tax. If that were done in the United States, the question is: Who will pay the costs, and what will the revenues be used for? Paggi asked.

In California, we have the beginnings of a carbon tax in the form of the cap and trade program, he said.

For more information on these reports or research conducted by CAB, visit the CAB website at http://www.csufcab.com or contact Paggi at mpaggi@csufresno.edu.

Back