California Agricultural Technology Institute

Raman spectroscopy explored for detecting wine spoilage microorganisms

Fresno State wine microbiologists are exploring a new method for helping the wine

industry to more efficiently detect yeasts and bacteria that cause sensory defects

in finished wine.

Fresno State wine microbiologists are exploring a new method for helping the wine

industry to more efficiently detect yeasts and bacteria that cause sensory defects

in finished wine.

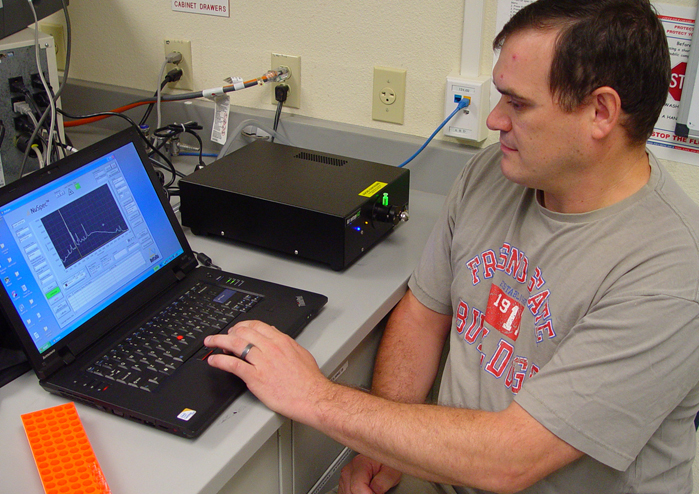

Susan Rodriguez, a research fellow for the Viticulture and Enology Research Center, is leading the work featuring the use of Raman spectroscopy to identify yeasts and bacteria that present a spoilage hazard. Enology Professor Roy Thornton is serving as co-investigator.

“Wine is the number one finished agricultural product in California, with an annual impact of more than $50 billion on the state’s economy,” Rodriguez said in outlining the need for the research. “However, wines which develop defects during fermentation are either subjected to expensive ameliorative treatments or are downgraded, resulting in reduced revenues for the industry.”

Many methods currently exist for detecting spoilage microorganisms (such as Zygosaccharomyces bailii) in wine during and after alcoholic fermentation, Rodriguez noted. However, most of these methods are relatively complex, expensive or require highly trained personnel to employ. Raman spectroscopy offers a potentially more effective, less expensive alternative.

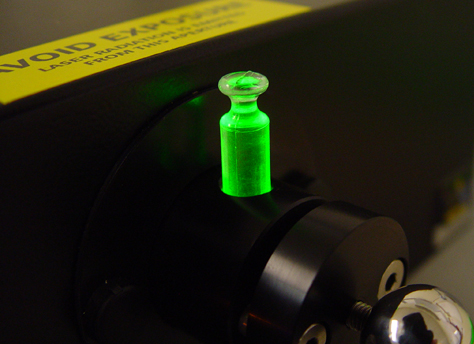

Named after the Indian physicist, Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, who discovered

the ‘Raman effect’ in 1928, the use of Raman spectroscopy has exploded in the last

10 years. It can be used to identify the chemical composition of materials s by detecting

slight differences in the energy of photons emitted when materials are illuminated.

Recent advances have enabled scientists to use the technology for investigating microorganisms

and their metabolic activities.

Named after the Indian physicist, Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, who discovered

the ‘Raman effect’ in 1928, the use of Raman spectroscopy has exploded in the last

10 years. It can be used to identify the chemical composition of materials s by detecting

slight differences in the energy of photons emitted when materials are illuminated.

Recent advances have enabled scientists to use the technology for investigating microorganisms

and their metabolic activities.

“Our laboratory has been using Raman spectroscopy for the last three years in an ongoing investigation into the quantification of microbial rot of grapes,” Rodriguez said. “It has shown great promise as a rapid, simple, and economic method of detecting spoilage microorganisms in wine. This would be valuable for an individual winery and for the industry as a whole,” she said.

The objective of the current project is to calibrate a recently acquired DeltaNu Advantage 532 Raman spectrometer so it can identify major wine spoilage yeasts, Brettanomyces/Dekkera and Zygosaccharomyces bailii, as well as strains of the commonly-used wine fermentation yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and wine spoilage bacteria, Lactobacillus and Pediococcus, as well as strains of the malolactic fermentation bacterium, Oenococcus oeni.

Additional objectives include developing calibrations for identifying combinations of bacteria and yeast and for predicting viability of yeasts and bacteria

A problem with light leakage in the Raman spectrometer, requiring shipping the spectrometer back to the manufacturer, delayed progress. Now part way through the study, researchers have been able to demonstrate accurate identification of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus and Oenococcus at the strain level as well as the genus level, Rodriguez reported. The work is continuing with the development of a calibration for yeast strains.

Overall the project prognosis is good.

“We believe that Raman spectroscopy can be a rapid, relatively inexpensive operation that requires virtually no sample preparation, and operator technical skill requirements are low once the instrument has been set up,” Rodriguez said.

Complete analysis and dissemination of results are planned for next year. Partial funding for this work was provided by the California State University Agricultural Research Institute (ARI), with additional support from the American Vineyard Foundation.

Assisting in the laboratory work is enology undergraduate student Jordan Randall.

For more information, contact Rodriguez at susanr@csufresno.edu.